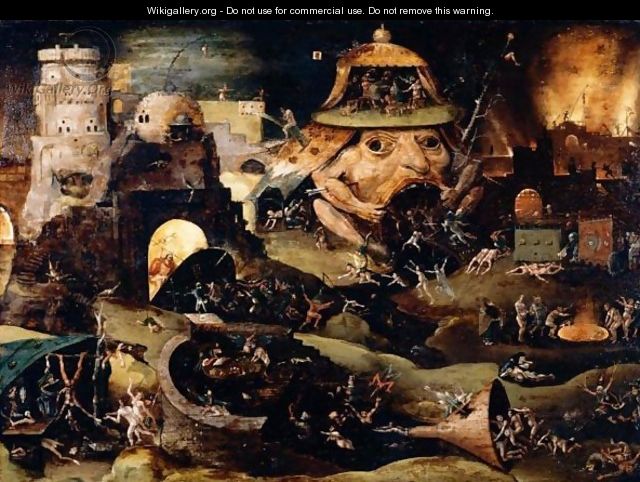

One of the reasons that most people have learned very little about Christ’s descent into “hell”, is a reaction to an overreaction about this part of the story in the early Eastern Church. “Christ’s descent” became the ancient equivalent of a superhero story. There are stories about Jesus being swallowed by Sheol and in Jonah-like fashion, Sheol vomited out Jesus and everybody else. You can still get a very popular story of the time on Amazon, The Gospel of Nicodemus. I read it on Ibooks. Stupid book, but it was free. It is about Jesus saving the Old Testament people from Sheol, but all the characters could only say lines that they had said in the Bible. Anyway, the fiction around this story became so thick that people couldn’t discern fact from fiction. Augustine expressed this complaint, and that seems to have carried down to the Reformers.

One idea that arose in the Eastern Church and remains to this day is that Christ’s descent was not only to free the Old Testament righteous, but also to bring a saving Gospel to the unrighteous. This bothers a lot of people. Some church bodies have expressed doctrines that your destiny is sealed at your death. Others basically have that same assumption without enshrining it as a doctrine.

Is there anything biblical to say or even suggest this? One comes shortly after the passage in 1 Peter mentioned earlier in 1 Peter 4:6:

For this is why the gospel was preached even to those who were dead, that though judged in the flesh the way people are, they might live in the spirit the way God does.

The chapter and verse number system was introduced to the Bible during the Reformation period. It is invaluable in helping us find stuff. But sometimes it gets in the way and makes us break up the context of the Bible in our minds. In this case, if you ignore the big number four and let Peter continue his thought, it seems pretty clear that the preaching to the dead referred to in this passage is the same dead Peter spoke of in 3:19. A more literal translation might be: “For this reason, the dead were evangelized”. The verb rendered here as “were evangelized” is what is called an indicative aorist verb. In Greek, this indicates past continuing action. One common interpretation of this verse is that it refers to the evangelization of people while they were living who are now dead, but that doesn’t quite fit the sentence. What is past is the evangelizing, not the people’s lives. What this sentence seems to propose is shocking. It says the dead were evangelized, and almost all of us assume that once you die the opportunity for evangelism is over.

This makes it sound like the preaching was a second chance for people who had disobeyed God during life and had not had an opportunity to hear the promise of salvation. Peter is acknowledging that the disobedience of these people resulted in their judgment—namely death in the flood and thousands of years in the agony of Sheol. But the purpose of this visit from Christ is that they might live in the spirit.

Obviously, this makes us nervous on one hand and relieved on the other. It has always seemed unfair that some would go to Sheol without the benefit of hearing the Gospel in some form, even though they are sinners and knew right and wrong inherently. All humanity deserves the judgment and cannot earn salvation, but cannot God be gracious to whom He chooses when He chooses? Can we say for certain that physical death marks the end of your opportunity to believe and be saved? Judgment Day could be the end of opportunity.

The main biblical objection to this interpretation is found in Hebrews 9:27:

And just as it is appointed for man to die once and after that comes judgment, so Christ having been offered once to bear the sins of many will appear a second time, not to deal with sin but to save those who are eagerly waiting for him.

This passage is not primarily about whether there is any chance of being saved after physical death, but it does make a statement about dying once with judgment assumed to immediately follow. This passage is essentially saying, “Just like we live and face judgment only once, Christ lived and died once, not over and over again. This would rule out a reincarnation scenario, but can we really say it precludes Jesus reaching out to someone in Sheol. As noted in an earlier blog about Psalm 139, Sheol is not quite yet forsakenness. The timing of the judgment in relation to physical death is not specified in the Hebrews passage. We just assume it to be immediate and final.

In one sense, judgment upon our death is immediate. The dead found themselves in Sheol and not Heaven. That is a judgment. Their residence in Sheol could be for thousands of years. But is it final? If it is final, then is Judgment Day simply perfunctory? I will say here that I do not know God to be simply perfunctory about anything. Everything has its purpose. Some treat baptism as perfunctory, for example. It isn’t. Baptism has a definite function.

Establishing that Jesus can, did or even does reach out to the lost in Sheol is a radical enough of a suggestion that one needs more than these somewhat obscure passages in 1 Peter. Another possible reference to Jesus liberating even some of the damned in Sheol is Psalm 107. Once again these words:

He brought them out of darkness and the shadow of death, and burst their bonds apart. Let them thank the Lord for His steadfast love for His wondrous works to the children of man! For He shatters the doors of bronze and cuts in two the bars of iron.

The phrase “doors of bronze” gets frequent use in non-canonical literature as a reference to Sheol. So if this passage applies, and I think it does, it is speaking about the “disobedient” rather than the righteous. Still other passages, namely Isaiah 42:7b and Luke 1:79, speak of “captives”. These passages are inconclusive, however, because they do not specifically say to whom they are referring.

For some early Eastern Church fathers and for the Orthodox Church, the teaching that Jesus preached the Gospel to perhaps save some of the lost or even all of the lost in Sheol is a big piece of their doctrine and liturgical life. They consider it to be simply logical that this process continues to this day. I will say I hope this is right.

Does this teaching do violence to any other understanding or practice within the Church? It certainly seems in line with the mercy and passion of God. It doesn’t necessarily suggest that everyone is saved in the end. We will see in a later entry that people are eternally damned and in great number. Some argue that a loving God couldn’t and wouldn’t damn someone eternally. They don’t understand the unchangeable nature of God’s Law. God clearly does damn people because of the requirements of the Law, but a loving God could pursue someone up until the last possible moment and that last moment may be Judgment Day rather than death.

If Christ did preach the Gospel in order to save in Sheol, wouldn’t everybody there repent and believe? I mean what sort of idiot would decline such an offer after experiencing such suffering? The rich man in Jesus’ story of Lazarus seems open to a change. Still, we might be surprised. Saving faith is not the result of even overwhelming proof. Faith is the gift of God to people who are able to receive it.

Whether Christ was giving the disobedient in Sheol a chance to hear the Gospel and believe is hard to concretely determine. At best, we can say that it is possible. This shouldn’t rob us of any motivation to share the Gospel among the living. People suffer in Sheol. If we care, we would want them to avoid this. If people become disciples while still living they can carry out their God-given purpose and even realize reward for it. We are rewarded for our faithfulness in this regard. Beyond this both love and Christ’s command compels us.