Many people are not aware of what Sheol is, so first let me give you a quick primer. Sheol is a Hebrew term used 65 times in the Old Testament. Its Greek equivalent “Hades” shows up another 10. It is not a reference to “Hell” as most people think of Hell. It is more the waiting room for Hell. It is not “purgatory” either. Though I would bet that an ancient misunderstanding of Sheol led to the development of the idea of purgatory.

Sheol has escaped many people’s understanding thanks to some lousy translating. Many versions of the English Bible cover over the word by translating it as “the grave” or “the pit”. This is garbage. Sheol is a place and a proper noun. Leave it as is.

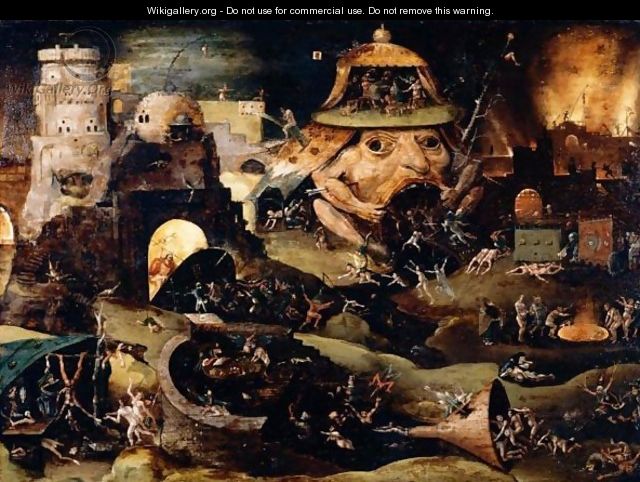

In the Old Testament everyone expected to go to Sheol whether they were considered righteous or unrighteous. It was the place of the dead. Jesus’ account of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19f) gives us the best glimpse into Sheol as it was.

22 “The time came when the beggar died and the angels carried him to Abraham’s side. The rich man also died and was buried.23 In Hades, where he was in torment, he looked up and saw Abraham far away, with Lazarus by his side.

Luke 16:22-23 (ESV)

Notice that both the rich man and Lazarus are in Hades (Sheol) but in significantly different conditions. Lazarus is in “the bosom” of Abraham, and the rich man is in torment. He explains the torment as being because of fire. Thus the confusion with the post-Judgement Day “lake of fire”, which we think of as Hell.

Lazarus, Abraham, and the rest of the Old Testament righteous are waiting. For what? For Jesus to complete atonement for their sins on the cross and for Jesus to complete the Law in a way that they did not with His life. Timing actually matters. You didn’t suffer in this part of Sheol. The Roman Catholic Church refers to this place as “The Limbo of the Fathers”. Others prefer “Abraham’s bosom”. I like “the good neighborhood of Sheol. It reminds you where it is. What did they do there (some for millennia)? Don’t know.

When Jesus had completed His work, He set them free.

As for you, because of the blood of my covenant with you,

I will free your prisoners from the waterless pit.

12 Return to your fortress, you prisoners of hope;

even now I announce that I will restore twice as much to you.Zechariah 9:11-12 (ESV)

You can see that they were rewarded for their patience and faith. Want to read more about Jesus’ descent into Sheol read here: https://afterdeathsite.com/2017/04/04/christs-descent-into-hell-part-4/

People like the rich man were/are waiting too. Without the forgiveness of Christ you are stuck in the bad neighborhood of Sheol until Judgment Day. Could actual Hell be any worse? Read this: https://afterdeathsite.com/2023/11/14/how-is-sheol-different-than-hell/

Those who now die connected to Jesus will never go to the “waiting room”. Eternal life in Heaven begins immediately.

Is there any hope once you find yourself in the bad neighborhood of Sheol. Many people and denominations say “no”. To be honest there is not a lot of Scriptural information on the topic. Those who say no are depending on one verse, which I think they misapply. It is Hebrews 9:27:

27 Just as people are destined to die once, and after that to face judgment, 28 so Christ was sacrificed once to take away the sins of many; and he will appear a second time, not to bear sin, but to bring salvation to those who are waiting for him.

Hebrews 9:27-28 (ESV)

You can see that the context is about how many times Christ is sacrificed. The answer is one. Similarly, how many lives do we live before judgment–one. It does not say the final judgment is immediate. There is the waiting room. The one Bible passage that suggests some measure of hope is 1 Peter 4:6:

6 For this is the reason the gospel was preached even to those who are now dead, so that they might be judged according to human standards in regard to the body, but live according to God in regard to the spirit.

1 Peter 4:6 (ESV)

“The gospel was preached to those now dead” is not a great translation. It is more like “for indeed the dead ones were evangelized (declared the good message)”. The context of “the dead ones” is found in 1 Peter 3:20. They are the disobedient people killed by Noah’s flood. They waited in the bad neighborhood of Sheol until Jesus declared the promise of salvation to them. Then some, if not all, were made alive to God.

How far does this second chance go? I don’t know. I hope far. It is clear that many make it through the waiting room all the way to their appointment at Judgment Day. Hell won’t be empty, and that is regrettable since what Christ did was big enough for all.